“], “filter”: { “nextExceptions”: “img, blockquote, div”, “nextContainsExceptions”: “img, blockquote, a.btn, a.o-button”} }”>

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members!

>”,”name”:”in-content-cta”,”type”:”link”}}”>Download the app.

Earlier this summer, I was hiking in the rain on Canada’s West Coast Trail when the path crossed under a large log. I lingered for a moment in the dry refuge, and noticed overhead the words “I love u” carved into the underside of the wood. I smiled, called my partner over for a selfie, then hiked on. On a crowded trail that’s riddled with reminders of human life, from lighthouses to wooden ladders and outhouses, I was unbothered by this small and hidden message. But not all hikers feel the same way.

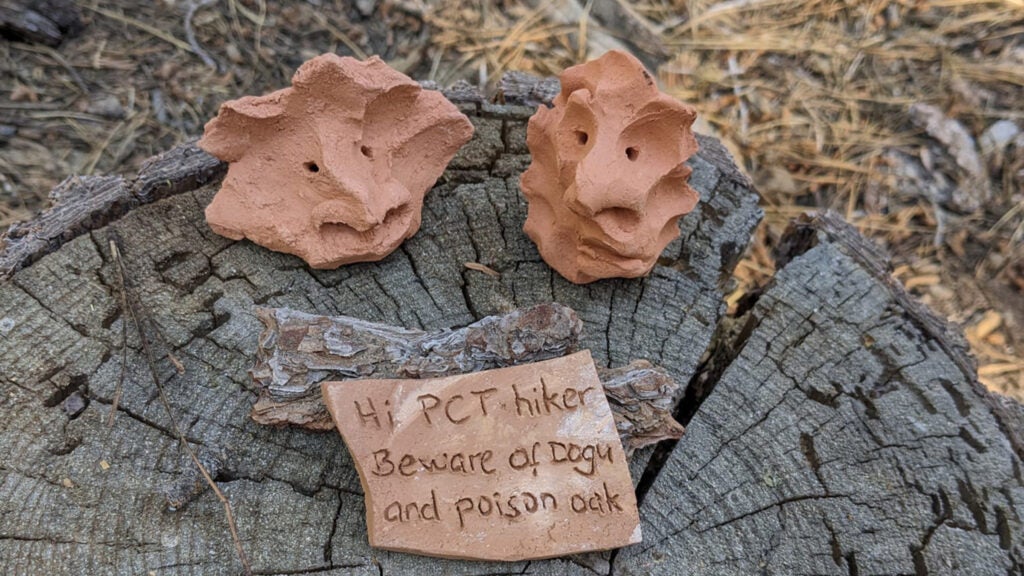

Recently, a hot debate broke out on Facebook about clay figurines someone is leaving along the Pacific Crest Trail. These sculptures, which hikers have found throughout Southern California, are small trinkets that appear to be handmade out of unfired clay. The whimsical humanoid faces are often accompanied by notes carved into a small shard of clay: “Hello PCT Hikers, Enjoy your journey!” reads one. Another warns hikers about poison oak.

We’ve all come across something similar along one hiking trail or another: “fairy houses” made of sticks, rock stacks along riverbanks, designs made out of pebbles on the ground. Some hikers delight in these surprises, while others detest them. Many experienced hikers are quick to call foul on Leave No Trace violations. But is there a line between harmless tokens of creative expression and true negative impact on the environment?

In response to those clay figurines, many Facebook users were loud and clear: Nature is no place for human art of any kind.

Commenter Kat Sink wrote, “I’m an artist and I love art but wild, natural places are not where these belong. In the wild, they are trash.”

Others took a more lenient approach: “Lighten up! A giggle on the trail from an artist is fine by me,” wrote Facebook user Mike Zawatsky.

Others pointed out that this problem is small potatoes in comparison to heavy littering that exists in certain high-traffic areas. “I’d much rather see a painted rock than discarded tissue,” wrote another commenter.

It’s a fair point: Stumbling upon a mouse-sized cabin made of twigs or a lump of clay that blends into its surroundings is generally far less offensive than walking a trail littered with Snickers wrappers and cloudy Mountain Dew bottles—and something easily dismantled or made of materials found in the area is unlikely to cause lasting ecological harm. But for some hikers, any aesthetic reminder of other humans detracts from an otherwise uninterrupted experience of nature.

I reached out to JD Tanner, Director of Education and Training at Leave No Trace, about the clay figurines. Tanner argued that leaving behind human-made items of any kind, however small, negatively impacts the environment.

“Leaving unnatural items along trails or in natural space can disrupt ecosystems, introduce pollutants, and diminish the pristine beauty that attracts people to these areas,” Tanner said. “Such actions can harm wildlife, spread invasive species, and degrade the outdoor experience for everyone.”

It’s worth distinguishing here between archaeological artifacts and modern objects abandoned by hikers. Indigenous people have left their mark on landscapes across the country in the form of petroglyphs, pottery, structures like granaries, and more. These items represent entire cultures of people who lived on and stewarded the land. Relics of historical and cultural significance should be left alone by visitors, and they stand apart from modern-day items left behind by individuals, particularly individuals who don’t have an ancestral connection to a landscape.

Whether it’s art or garbage in question, Tanner asserts: “To preserve these environments for future generations, it’s crucial that we pack out everything we bring into our outdoor spaces.”

When it comes to lighthearted, low-impact creative displays on the trail, it can be easy to roll one’s eyes at those who advocate for stringent adherence to LNT principles. But it’s important to keep in mind: trash begets trash. Once human-made artifacts are introduced to a trail, new hikers may take it as permission to leave a mark of their own.

You’ve likely seen such displays in action: Take, for instance, an area where tree bark is riddled with carvings. Carvings leave trees vulnerable to pests and disease and, especially in large groups, they’re an eyesore. But when hikers see one set of initials carved into a tree beside the trail, they figure it’s OK to follow suit. Before long, one carving has turned into many, and an entire grove of trees has been damaged. Even seemingly innocuous ornamentations can introduce a slippery slope of human impact to a trail, park, campground, or area.

Nature itself does a pretty good job of surprising and delighting on its own—but there’s still room for creativity in the backcountry. Take rock stacking as an example. Leave No Trace doesn’t condemn the practice altogether, but offers guidelines that honor both freedom of expression and conservation. This article by LNT educators recommends leaving officially designated cairns undisturbed, stacking rocks on durable surfaces only, collecting rocks from loose soil where erosion is unlikely, then dismantling your stack and returning rocks after taking a photo or two. The same standards can be applied to structures or designs made of sticks, leaves, or other natural materials.

All in all, it’s important to remember that at best, aesthetic disruptions to nature can have a negative influence on the experience of other visitors. At worst, they can harm wildlife, disrupt ecosystems, and kick off a cascade of human impact on the land.

In a comment on Facebook, Dave Mez summed up a sentiment many hikers share: “Nature is the art I come to see.”